Pop culture loves its pop culture references. They say nostalgia is in right now, but the truth is that nostalgia has always been in, and it will always be in, and we only act surprised when the focus shifts to a different decade. But nearly 20 years ago, before the wide-spread saturation of nerd culture across mediums, there was one show that used pop culture with devastating effectiveness. That show was Farscape.

Look, this is how it works now: Even outside of narratives that are set in times past and geared toward this sensibility (think Stranger Things), plenty of stories are built on the framework of nostalgia. Ready Player One is the convergence of that brand of fiction, a veritable pop culture buffet that was so explicitly tied to a place and a time that Steven Spielberg felt the need to alter the source material when adapting it for the screen so that it wasn’t one large reference to his own early work. Knowledge of nerd tropes in these narratives translate to literal power. If you play D&D, if you know Back to the Future, if you’ve watched enough Star Trek, you win. The day is yours. Geek culture will raise you up.

Without these frameworks, references to pop culture within fiction is often used for the sake of humor. The Marvel films are chock full of these jokes: Captain America “understood that reference” to The Wizard of Oz; Spider-Man keeps using plots points from “old movies” to defeat people; Star Lord is the literal embodiment of a mixtape. The Magicians does an episode with “Under Pressure” karaoke; the Doctor’s companions call him “Spock” when he’s acting extremely capable; Supernatural had a Scooby-Doo crossover episode because why the hell not at this point? Sometimes these narratives are purposefully deconstructed—as Avengers: Infinity War seems to have done—pointing out that pop culture may be enjoyable but it cannot save your life when a real threat shows up. But really, that’s just a play on what Stranger Things and Ready Player One are espousing; pop culture either prevents the really big scary things from coming for you, or it suddenly, horrifically, fails you when you need it most.

There is nothing wrong with being excited over familiarity and shared experience when this happens, but there is something particularly discomfiting about the level of recycling that we’re seeing in the current pop culture zeitgeist. It seems now that everything has to contain a clever reference (or several of them) in order for anyone to care about consuming it or analyzing it. And that’s a shame because there is a way to do this with meaning. There is a way to have these conversations, to really talk about how pop culture shapes us and guides us and, yes, even sometimes saves us.

Farscape did this. Farscape was this. Farscape wanted to show you how it worked. Because all those geek references aren’t going to save you through action—they’re going to save you through context. It’s not that these references are out of place; far from it, in fact. It’s just that we neglect the true use of what we absorb. We forget the real reasons why pop culture can matter.

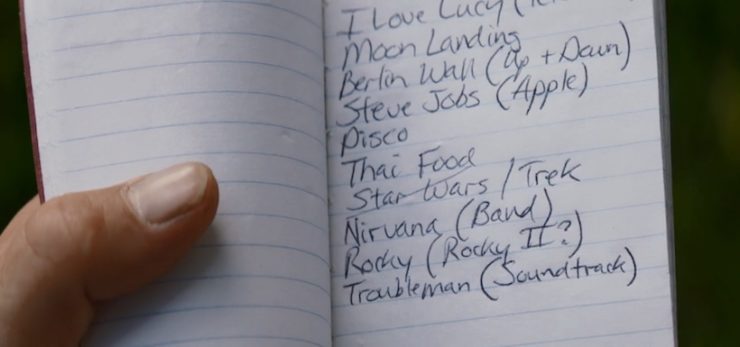

Think back to The Avengers. Captain America begins this story completely out of his depth, the guy who has missed out on seventy years of movies, video games, theatre, and so much more that he can’t begin to quantify. (By his next film, The Winter Soldier, he actually has a notebook full of mile markers that he’s missed, music and movies and historical events that he needs to get straight.) Tony Stark makes a reference to some SHIELD employee secretly playing Galaga, and Steve Rogers turns his head, an expression of inquiry on his face: Should I know what that is? Is it important? What am I missing? Then someone makes a reference to The Wizard of Oz, a movie from 1939 that he’s seen, and it anchors him. “I understood that reference,” he says proudly as Tony rolls his eyes. Because Steve has been grasping this whole time, and something finally makes sense to him. It helps him keep his head in the midst of everything he doesn’t know.

This is what Farscape does every. damn. episode.

John Crichton—the better Buck Rogers, the galaxy’s wobbliest astronaut, the everyman’s everyman—is tossed through space to another side of the galaxy. He is given a helpful injection of translator microbes so that he can understand the languages of the aliens around him, but that’s about it. Everything is a mystery. Everything is magic. Everything is unthinkably dangerous and overblown in the worst possible way. He can’t sneeze without offending someone. He can’t move without stepping in alien crap. Any reasonable human mind would go completely mad in those surroundings and, to an extent, that’s exactly what John does. He has one mechanism, one trick, that keeps him semi-functional: he relates everything to pop culture that he already knows.

In the first episode of the show, John reflects on where he is and how different alien life is than whatever he had anticipated. “Boy was Spielberg ever wrong,” he grumbles to himself. “Close Encounters, my ass…” Because if you had to come up with a reference to first contact, you’ve got just a few on hand. And as John hit space exactly one year after Star Trek: First Contact hit theaters, you can bet he’s going to go with the Spielberg version. We instantly know more about him, but more importantly, we can see how he is framing his experience to get a better handle on it. This is a coping device.

John Crichton couches everything in familiar terms because there’s no way for him not to do that in his circumstances. He’s on a living ship, lightyears from home, sharing close quarters with a bunch of escaped alien prisoners. At one point, he asks their ship’s pilot to put a “tractor beam” on another ship that’s running from them, and no one has a clue what he means. He tries other terms that make sense to him—graviton field? Attracto ray? Superglue?—only to find out that they call it a docking web. Oh well. He tried, right? They land on a swamp planet and he tells former-Peacekeeper commando Aeryn Sun that the planet looks like Dagobah. “You know, where Yoda lives.” Aeryn proceeds to assume that Yoda is a real person, as John told her that the “little green guy” trains warriors.

John Crichton’s pop culture references don’t save anyone but himself—and that’s the point of the show. John is a scientist and an ’80s kid and a great big nerd, and he has the same reference points that the rest of us do. In the face of the unknown, he has no choice but to try and contextualize everything he’s seeing. He calls his Hynerian shipmate Rygel XVI, a former dominar to over 600 billion subjects, names like Spanky and Sparky and Buckwheat and Fluffy because that’s the easiest way to handle the regal, tiny con artist. When he has to provide fake names for himself and Aeryn, he tells everyone that they are Butch and Sundance. He talks to her about her “John Wayne impression,” aka, the way she always walks around swaggering and heavily armed to intimidate people. John’s new friends learn that this is simply what he does, and stop worrying when he brings up things and people and places they’ve never heard of. Eventually, they even start to pick up his slang, albeit inexpertly (“She gives me a woody.” “Willies! She gives you the willies.”), and his games (“Paper beats rock.” “That’s unrealistic.”), and his even his attitude (“Chiana has already told me a few words: ‘Yes’, ‘no’, ‘bite me’, that’s all I need to know.”) They marvel at how a being from such a primitive species manages to keep up with them.

At a very pointed moment of the show, John comes to a realization about his place in this universe: “But I am not Kirk, Spock, Luke, Buck, Flash or Arthur frelling Dent. I’m Dorothy Gale from Kansas.” His current avatar doesn’t amount to any of the heroes he tried to emulate growing up, but to a young girl who is lost, far from home and everything that makes her feel safe. John Crichton checks in on those pop culture narratives that shielded him in his youth and finds that he can’t pretend to their levels of bravado and knowhow. He may be a smart guy by human standards, but among aliens, he’s middling at best. The only thing that allows him to navigate high-octane threats is adrenaline response and his tendency to be unpredictable by the standards of people who don’t know his species.

And it gets worse from there.

John Crichton is accidentally gifted with an abundance of wormhole knowledge, given to him by an ancient race who mean to provide him a way back to Earth. But a Peacekeeper commander named Scorpius is determined to wrestle that knowledge from him, so he implants a neural clone of himself in John’s head; an imaginary friend version of Scorpius that only John can see. John dubs that Scorpius replica “Harvey,” after Jimmy Stewart’s invisible, 6-foot tall pal. Every interaction between John and Harvey is peppered with pop culture references, as they are both limited to what resides in John’s brain to form the bulk of their interactions. John takes Harvey on a literal rollercoaster in his mind, puts them in war films and vampire films and 2001: A Space Odyssey, he has Harvey hang around playing the harmonica while wearing Woody’s (from Toy Story) boots at one point, complete with Andy’s name written on the sole. The only way to keep Harvey at bay is to keep him busy—John’s pop culture sinkhole is his only means of sanity. The longer he’s away from home, the more he learns to rely on it.

John Crichton isn’t a hero because he is strong, or tough, or ultra capable. He is a hero because, when you watched him react to the circus sideshow that his life had become, you can’t help but think I would do the exact same thing. No tales of derring-do in the traditional sense for Farscape; instead, John has to keep it together with nerve, weird weaponry, and a well-placed reference that no one else in the room understands. He is the talking person’s hero, chattering endlessly until he hits on the thing that makes him friends or saves his ship or stops an awesome military power from invading another part of the galaxy.

This is a huge part of what makes Farscape so riveting. John’s ability to use those references is always humorous, but it also brings home just how frightening and truly alien his surroundings are. He’s dragging together a framework that allows him to keep operating under unbelievably high stress scenarios, where losing his mind is never far from his mind. When his friend D’Argo knocks him into a coma, John’s unconscious brain converts his reality to a Looney Toons-esque animated mockery of the situation, helping him to work through the trauma.When John is isolated on another Leviathan ship all alone for months, he teaches a Diagnostic Repair Drone (DRD) to play the 1812 Overture for him while he works on wormhole equations. When he’s terrified to face more abuse at the hands of Scorpius’s Aurora Chair, he cites Monthy Python or Lost in Space. In the darkest moments, he always has something to reach for… and he always makes it out the other side.

Farscape somehow recognized the most valuable lesson in the nerdy knowledge we cling to; pop culture won’t save us by giving us plans to mimic, or because it’s closer to reality than we think, but because it is a language to understand the world by. It will save us through references and memes and the jokes we tell when we’re frightened or uncomfortable. It will ground us when we’re uneasy and alone. It will shore us up against the unknown, no matter how painful or sinister. It may not make us superheroes—but it does keep us from falling apart. There is power in our shared languages and experiences, power in how we view our lives through the prisms of story. And we would do well to remember it whenever we’re lost out there in the Uncharted Territories.

Emmet Asher-Perrin will never be done talking about Farscape, and how perfect it is. Ever. You can bug her on Twitter and Tumblr, and read more of her work here and elsewhere.

I love how much you love Farscape lol

I admit, I <3 Farscape, and thus, am pretty predisposed to love this article as well. I get a strong recognition vibe out of these thoughts too. Admittedly, I am not so frelling out of my depths as John Chrichton, but out of all the many pieces of pop culture I have dunked my brain into, those I revisit most often are those that most help me. For me, it’s Harry Dresden, constantly feeling one step from total disaster, severe authority issues and anger management problems, and yet, can set all that aside and force himself to think through a problem, find the right place, the right time, the right thought (it helps that, just like Chrichton, he thinks in Genre Savvy).

A Farscape article was not what I expected when clicking on the title. But I do love John lots.

Exactly. John Crichton’s pop cultural references feel very natural in his fish out of water situation, whereas many others feel so contrived, like winking at the audience.

So, there is: “something particularly discomfiting about the level of recycling that we’re seeing in the current pop culture zeitgeist”

Given the rest of the article, what does that say about how people are feeling about their world?

Cap’s experience is a bit akin to all of our experiences in childhood. In the 1980s as a kid, all I kept hearing was how everything that ever happened that ever mattered had happened in the 1960s. I half believed it, until in the 1990s it was the 1970s that were all the rage … etc. I’ve enjoyed looking back on the 1980s and 1990s. Now it’s going to come full circle, where nostalgia will soon involve looking back on stuff post-2000 after I stopped paying as much attention, and one again I can no longer relate.

Thank you for your thoughtful article. While I enjoy a good pop-culture reference, I have recently felt that the prevalence of these references in tv shows & movies has become contrived much of the time.

Farscape is one of my all-time favorite tv shows. When I watched the show in its original run, I enjoyed the pop-culture references and the blank stares and head-shaking that was returned. Despite that, John continued to express himself through pop-culture references not seeming to care when his companions ignored him or questioned his sanity. The Wizard of Oz is a running thread through the whole series. Also, quite a bit of both Star Trek & Star Wars. I felt right at home.

Through Farscape message boards, a friend & I discovered that many international Farscape fans were just as confused as Aeryn, D’Argo, Pilot, and the rest of Moya’s crew. We created a website called Crichtonisms (still available through the Internet Archive Wayback Machine-go back to 2007/2008) to explain these pop-culture references (and some American idioms) to our fellow fans. My friend & I loved the the references & would watch each episode multiple times to make sure we got them all. We identified with John as fellow-geeks but also as ordinary humans who would freak out when confronted with his situation.

The last paragraph really sums it up so eloquently.

“…pop culture won’t save us by giving us plans to mimic, or because it’s closer to reality than we think, … It will save us through references and memes and the jokes we tell when we’re frightened or uncomfortable. It will ground us when we’re uneasy and alone. It will shore us up against the unknown, no matter how painful or sinister. It may not make us superheroes—but it does keep us from falling apart.”

Amen to that!

Really cool article, except for the fact that Farscape doesn’t seem to be available anywhere. I personally own the DVDs, because I was obsessed. I want people to be able to read your article and then experience the real thing! We haven’t forgotten…how can we share this awesome show?

What, no mention of The Orville, the show that literally used Keeping Up with the Kardashians to save the day? And used Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer to teach a main character an important lesson about acceptance?

That was beautifully written and somehow made me love Farscape all the more.

@9 The Orville is pretty much verboten around here because it ruined Star Trek Discovery’s big return. We were just supposed to be so grateful that Star Trek was back on at all that we’d all accept its Game Of Klingons rubbish without dissent. Then The Orville went and spoiled that by giving us a blast of old school fun and bright colours which reminded everyone how much we loved the TNG era, and it made STD have to work for its audience instead of just be granted it and also gave STD some very uncomplimentary comparisons which made it come off as second best to The Orville more than once.

No mention of Galaxy Quest as counter-point? Farscape showed us a galaxy that doesn’t conform to our predictions, so pop culture offers us no solutions, only ways to create a thought frame, to get a handle onto what’s really going on. Galaxy Quest showed us a place where we’d accidentally predicted *exactly* how the universe worked, so closely that an alien race assumed that is was an historical record. A galaxy that required a team of genre-savvy geeks to save the day.

They used to say Nostalgia was a thing of the past. Now it seems like Nostalgia is the future.

I wish things would go back to the way they were.